EXIT REVIEW – BEECH – DE-FIGURING

The body has been the primary source of architectural metaphor beginning with our first surviving architectural text. But the status of that body is constantly in flux, its nature constantly being re-evaluated. It has haunted the discipline, manifesting its proportional perfection as temples, it's authenticity as material truthful-ness.The body has been idolized, denigrated, mutated, but never ignored.

It speaks a great deal about us in all ages, the manner in which it has been considered. The politics of our bodies’ relationship to technology, power, and each other evolves with new methods of visualizing the figure’s presence in space. I believe its time again to take stock. What has the body meant for architectural design, what could it mean, and what new potential could it present in architecture today?

My talk is about De-Figuring, by which I mean something very different from dis-figuring. Disfigurement implies broken-ness. De-Figuring is about new potentials. By disrupting the singular identity in the belief that new authentic forms of engagement lie beyond this contamination.

In his essay “The Natural Imagination", Colin St John Wilson discusses Freud and the oceanic feeling of attachment between the infant and mother as a sheltering all enveloping environment from which we later split to form our individual identities.

The creation of the other is directly related to this duality of enclosure and open space. Wilson quotes Adrian Stokes saying, “…The role of the masterpiece is to make possible the simultaneous experience of these two polar modes” By championing Stokes, Wilson makes the case for an architecture where identity is muddier, more ambiguous, dreamlike, and unreal.

De-Figuring then is about this collapse, and the methods by which this simultaneity can be evoked.

In the history of painting the frame acted as a window into another world. The frame terminated paintings simulated spatial depth and registered the divide between art and life in a manner analogous to the pedestal in sculpture. As an act of mediation, the pedestal and frame represented latent boundaries between the real and unreal. As sculpture stepped off its base this vestigial distinction was excised, sculpture invaded the space of the viewer unbounded.

The distance between the artist and site of expression got increasingly smaller until it reached a singularity in the 1970’s with Performance Art. Duration replaced Mediation as artists like Chris Burden and Vito Acconci operated on their own bodies.

In “Trademarks” Acconci bites his skin, he is temporarily marked with identifying dental impressions which he records on paper like a signature.

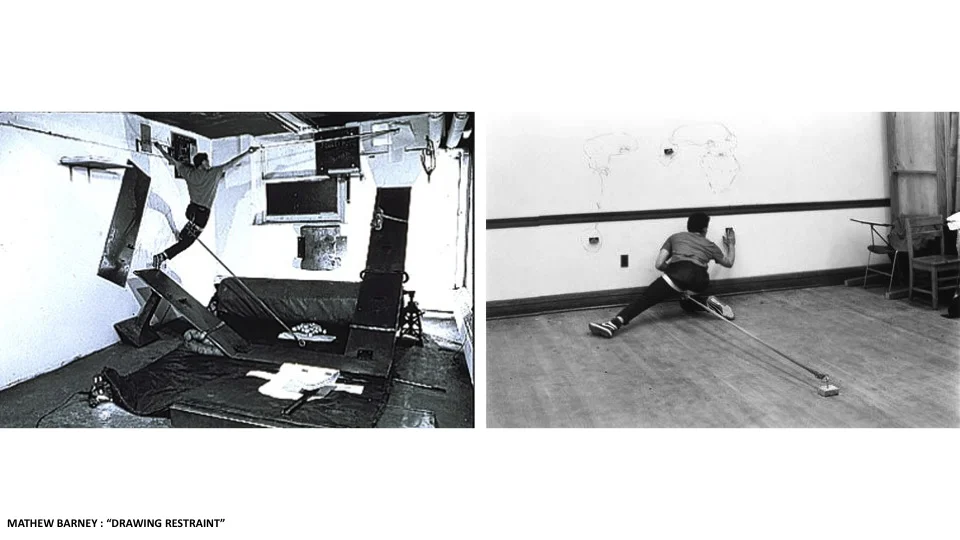

In “Drawing Restraint” Mathew Barney challenges the limitations of his physical body to make a mark through bondage and the weight of gravity, both methods connect the physicality of our bodies with the painful quest for agency. That both artists were concerned with authenticity shows that the collapse of author and method contained new potential for expression that was contested and therefor potent in dealing with the body politics of their era.

In their first monograph “Flesh” Diller and Scofidio posit an architecture of extended interface. The body incorporates tools, meaning they become extensions of us. For them, the architectural potential lies in designing that interface between the extended self and a newly defined reality.

Works of theirs like, “Moving Target”, use projection and choreography between real and prerecorded dancers to create a singular hybrid performance. Time is destabilized as Image and Object respond to one another. This Interface between surveillance, exhibitionism, camera, and eye goes a long way to describe how technology has become of the body and alien to it.

In their project “Facsimile”, a large screen scans across the façade, thickening it to incorporate the mundane encounters of office life like changing light bulbs which has the effect of humanizing the faceless-ness of corporate architecture. But many of these early projects, as interesting as they are, become mediated through some apparatus, whether it’s a mirror, a screen or any number of contraptions.

All of which harken back to the pedestal base as arbitrator of that interface.

The first documented use of the word “interface” dates not to the proliferation of personal computers, but 1882 when Edison electrified a square mile of lower Manhattan. It seems a rift was made in the continuity of the real with the invention of simulated day. Electric light extended the day, and habits changed, as New York became ground zero for the first electrically supercharged bodies.

Since then technology has evolved a much more intimate relationship to the body. Computers digitize our memories, biometrics replaces our faces, and deep brain stimulators regulate our happiness. The electrical impulses of our brains seem directly tapped into the grid, an ever growing umbilical cord of power strips, Wi-Fi, and files upon files. Identity is coded into Facebook pages, search histories, clicks, and likes. The object of the body is all but absent, slowly de-figuring to something irreducible.

I’m interested in how architecture can engage our increasingly simulated selves.

In Contemporary architectural practice Andrew Atwood produces Machines that probe the politics of the architectural figure. They are like mechanical performances; the machines and their products are inextricably linked. His “Plastic Thing Dropper” draws lines through space, tracing the dance of the machine like the motion studies of the Taylorists. It evokes our disciplines history with machines and spectacle simultaneously.

Andrew’s work identifies a new interface, simulations interacting with other simulations in new authentic ways. It’s like a double negative making a positive. He writes software to run machines, which produce objects.

The harnessing of the machines own mechanical limitations produces its effects. The qualities of messiness, the blips, pauses and errors reveal the internal logic of the structures while diagramming the lack of autonomy from external forces. Embedded in the object is the meaning itself, the models and drawings on his website stand alone, without descriptive text and often without titles.

This is his Project 1 from Machine 1.

The Machine essentially extrudes filament guided by servomotors like a homemade 3d printer. The manner in which it does this however, its method of drawing the figure carries with it the traces of the tool. This strange kind of autonomy is what draws me to Andrews work. There is simultaneity between the mode of representation and the object of design.

This is my recent entry for the Taichung Cultural Center Competition.

The Cultural Center typically reflects a delusion of unified cultural perception, I used the aesthetic of collapse as a method to de-monumentalize the figure, Which I think reflects cultures as a changing condition rather than heroic achievement. For this reason I wanted to design a building that read as monolithic from the park, But split into two languages as you walked around it to the street. It contrasts the strong form of the “L” shaped block and the vague forms that adjoin it. The apparent difference of these two languages is obscured on the interior through the repetition of the oblique entries in the reading room. The strong and weak forms carve and slip past each other creating ambiguities about your spatial location within the structure. I wanted to delay the sense of arrival by thickening thresholds to curate an aimless circulation. Producing this project I began working back and forth between 3d modeling and animation procedures to document and edit the form serially.

This is a still from a version of the animation, which shows a kind of continuity forming between elements of the interior and exterior. The working back and forth encouraged registers and durations within the form analogous to key-frames, embedding in the architecture that trace of the animation software. I recognize however that serial editing is not the same as the simultaneous relationship I admire in Atwood’s work.

The effects I discovered from cross-pollinating two programs though were productive for future investigations in my work. It allowed me to scrub through the video and examine the architectural figure in various states of creation and erasure. This scrubbing raised serious interest and concern for me in relation to the body.

If the body as it has been known is no longer the repository of identity, if we are, like Liz Diller says living disembodied lives, then one task of the architect is to reconcile with this displacement to find new sites of connection. In order to engage the disembodied body, architecture can de-figured itself through erasure.

Erasure as a process seems on the surface mostly contradictory to architecture. The practice of architecture is predicated on bringing things into being. Spatial Ideas are drawn as lines on paper which are translated into structures. I wanted to know if could reverse engineer this logic to make figures produce and address new ideas about the body.

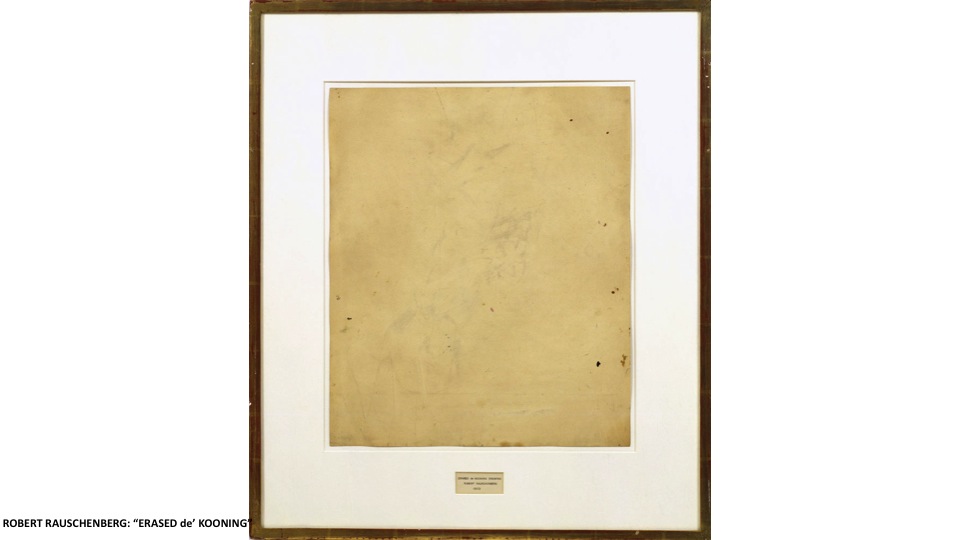

This drawing by Robert Rauschenberg became my starting point.

In 1953 Rauschenberg hung this work in his studio. It was notorious in his circle more for the mystique of its story than what it depicts. He called it “Erased De’Kooning”, which is haunting because of the association of mark making with identity, like something tangible was truly removed from the artist with an erasure. The drawing, meticulously rubbed out brought something new to life. The diminishing value of the object increased the signal of the text.

The title becomes an epitaph, it reconstructs the image as an anti-drawing. It draws attention to the absence the artist made. What could be architectures analog for the anti-drawing? What qualities would an anti-architecture produced through them possess?

I revisited that drawing by examining the works of Aldo Rossi and John Hejduk, scrubbing methodologies of figurality together to find out which would rub off. I unfolded and refolded canonic works of both architects producing monstrous figures like de’ Kooning’s sketch

This is my Erasure Model.

I slowed the sequential process of erasure producing a scrolling section plane that captures traces of the previous monsters intersected with serial cuts. These traces of contact register boundaries but resisting figuration. The form is emergent and conditional as transparency and overlap replace the closure of discrete objects.

Thom Mayne produced a similar model for his entry to the “Idea as Model” exhibition.The similarities are uncanny. But Thom’s model is mostly frontal, it recapitulates the palimpsest drawing and deals with issues of representation through section. But mostly I read the emphatic object-ness of the mass of acrylic. The model insists on its own presence.

My Erasure model relies on a binary of acrylic and air to be both complete and incomplete, A fragment and an abstraction of the same thing I constructed it as an anti-model, not as a representation of the objects themselves …

…but the trace of two intersecting systems.

The binary relationship is significant to me. It exposes that there is a difference between absence and void. Absence is charged by the denial of expectations and contradiction.

This is Raimond Abrahams project, “House without Rooms”, also from the “idea as model” exhibition. The relationship of the figure and ground between the 3 riveted plates shows an exchange that makes separation impossible. Look at how the plane carves the ground and house as if they’re one. Through the impartial aggression of the section plane, the house becomes monumental and totally interior, it constructs a contradiction of terms that begs whether something has been lost or gained. Erasures potential here lies in its ability to animate the section of the figure, breaking down its autonomy, by breaching its envelope. It’s an interesting contradiction to note especially given Eisenman’s language of cutting the 9 square grid as a demonstration of autonomy.

In Sylvia Lavin’s essay, “What good is a bad object?” she equates cutting of this type with punishment. She points to House 6 and the brutal attack Eisenman’s unleashed against it for its object-ness. She says, “…it was good for buildings to get sliced, attacked, blown to bits, hidden, and drowned, since the attacks on these bad objects made good political action seem possible.” But cutting can be a lot more than punishment, it can be operative and put to work through dissection. Cutting constructs precise registers between absence and presence that re-invokes attributes of the critical project’s obsession with the self and other.

The system of serial cuts as an analytic technique is probably most widely recognized outside the discipline in CAT scan images.Its history is however significantly older and useful for tracking the bodies abstraction as we continue to de-figure.

Michelangelo for instance, produced his sculptures by submerging his wax study models in a wooden box filled with water. As the water slowly evaporated he carved the emerging forms in the stone. This water coffin method de figures the model, producing an archipelago of body parts. The water surface acts as the cutting plane. Everything above the water’s edge is abstracted to pure form, the portions below do not yet exist.

The image on the screen is from Gideon's book, “Mechanization takes Command”. It shows Flesh becoming Meat.

Look how the body of the pig is transformed, its orientation changed, it hangs like a bag of grain, and skin becomes a convenient container for something far more valuable. The superficial surface that we are known by becomes irrelevant when cutting. Because cutting is after something deeper.

Cutting is a transformative act; it’s like alchemy, allowing us to move between objects and data. This is Durer looking through his drawing machine. Through his contraption he transforms a woman into a lute through the same dispassionate analytic system. The Grid he looks through objectifies her and the instrument, converting them to coordinates. The grid is his guarantor of truth, a mechanism for abstracting the body to define forms that evade the eye.

Piero Della Francesca’s orthographic drawings of the head reduce the figure to points in space. The body becomes data, a point cloud of information from which identity is carved out, bracketed, and defined. This transformation obviously has resonance with contemporary notions of the disembodied body.

Its common practice for beheading to be the first cut because the removal of the facial facilitates multiple identities in the same way that reducing the object of the body allows us to define and redefine ourselves. The face produces ideas of the whole and makes actions against it daunting. Surgeons recognize this and drape the body, erase its context and in doing so produce the operable site.

Sterility helps makes intervention possible

So what are these operations?

This is a set of diagrams I produced, which shows a sampling of my inheritance as a person entering the discipline. These are all methods I have adopted from our catalogue of techniques, which de-figure, disrupt, extend, multiply and divide the architectural figure. Some are as ancient as architecture itself, and some come from our long history of borrowing from other disciplines.

Shadowing is one of the techniques I have deployed in much of my work. I was influenced by Aldo Rossi’s shaded elevations where the harsh temporary shadows cast across the form became fixed in place with heavy black lines -

-As well as the paintings of Francis Bacon. The way the figure pours out onto the plinth and ground, through thresholds, suggests possible ways that de-figured architecture could situate itself in the city. By disrupting the otherness the figure is read against. Shadowing creates continuity and registers the occluded in traces that could expand architectures presence beyond the site.

Contemporary bodies are not only more decentralized and dissipated into our surroundings, but also contaminated. We now know that the body contains more than one code of DNA. We know that the bacteria in us outnumber our own cells 10 to 1; our bodies are not understood as autonomous agents but ecologies of mutual benefit. Superposition then seems like a necessary architectural reflection of our newly understood status. Parasites and chimera push architecture beyond composition to construct a language of conflicting conditions rather than unified wholes.

Effects of reflection in architecture range from invisibility to ostentation. The Modernists were the first to have enormous panes of glass with which to communicate uninterrupted messages.Mies was famous for his creative use of reflection to make the architectural object double, mirror, and disappear. Glass, chrome, match-cut marble and still planes of water make The Barcelona pavilion a tour – de – force for reflection. But, Modernity’s smooth planes were more than hygienic, they became agents of change addressing culture psychologically.

In his essay, “Critical Architecture” Michael Hays writes of Van Der Rohe’s Alexanderplatz competition that, “…each glass walled block confronts and recognizes nothing but its double. Like two parallel mirrors, each infinitely repeats the other’s emptiness“. He goes on to describe a position for critical architecture that does not embody the dominant cultural values or autonomous formal systems but “…places before the world a culturally informed product, part of whose self-definition includes the implication of discontinuity and difference from other cultural activities.” Reflection to Hays puts architecture alongside culture rather than in it.

This is Josiah McElheny’s piece title, “Modernity circa 1952, Mirrored and Reflected Infinitely”. The viewer gazes into the work through an opening covered with one-way mirror. The irregular glass vessels reflect a hidden light seemingly infinitely.The sterile case produces utopia as a closed system where your own reflection is excluded. The way these two examples use reflection is not just as a mirror for the vanity of dominant culture. And it’s certainly not for the paratactic parlor trick of reflecting reflections. The reflections I’m interested in are critical and informed but not at the cost of putting architecture outside culture or excluding presence.

Peter Eisenman gave a lecture titled, “A Critical Practice”, where he states that the paradox of architecture is that it is predicated on shelter and thus must be built while simultaneously dislocating itself. Reflection then becomes a method negotiating between the necessities for presence and disrupting autonomous otherness which disarms us from participating directly in culture.

Now all of this is not to say we do not have new method. We have new methods.

The aesthetics of the tool I talked about with Andrews work is one, but to a greater degree there are new methods of representation emerging as potential ways of locating the disembodied body in this de-figured architecture, and locating this de-figured architecture within our cities.

Infrared photography recovers De’Kooning’s drawing in much the same way that these new methods could locate the displaced figure in architecture

There is a growing trend in archeology to use minimally invasive methods such as ground penetrating radar to replace excavation. Deep study of the ground can be viewed without disrupting registration within the soil. These images preserve contextual properties of proximity and use associated with archeological artifacts that is traditionally lost when the object of study is unearthed. When compared to explicit representation of figure and ground like the Nolli map, you can see that the reading of figure IN ground is more about reading the signal from the noise. I’m interested in these representations and what they could mean for de-figured architecture as we consider its relationship to the urban environment and ground.

FOA’s port terminal becomes a seamless urban landscape which extending the city beyond its actual landmass. This new landmass is both synthetic and authentic, figure and ground.

Eisenman’s City of Culture in Gallacia uses deep cuts to reveal the constructed landform, imprinting on the mound the logic of the street.

MOS’s scheme for Orange, New Jersey populates the street and disrupts the reading of the grid. Architecture supplants the domain of the car to reintroduce the complexities of the walking city. The software driven organization of houses, offices, and shops fit together imprecisely forming nooks and courtyards which produce figure ground as urban noise.

Another emerging contemporary method of visualizing the figure and its relationship to space comes in the form of laser survey scanning. Still mostly in its infancy, I’ve begun to study this scanning technology and the effects the visualizations it produces have in regards to my interest in traces of contact, overlap and transparency. Currently, this technology is used for constructing as built documents and preservation studies for endangered monuments, a kind of conventional digitizing for posterity like a moratorium on decay.

This images produced by Scott Page begin to show promise of possible design value. It exist somewhere between Art and Architecture. Like Rachel Whiteread’s casts of stairwells and houses, space is given presence.

Images mapped onto the 3d model approximate qualities of light and materiality, It seems undeniable that the fantasy of virtual reality will become a real site for architecture as one of our expanded definitions of habitation. In these scans the human figure is absent but present though habit, use, and traces of interface. As the laser scans the superficial surface of the room it records wrinkled sheets melding into walls. Chairs melding into the floor, and drapes becoming faceted apertures. Architecture is very good at making boundaries, but images like this begin to suggest a blurrier spatial sensibility. Walls seem less solid. Surfaces seem softer and more pliant. Furnishings and frame melt into one another. These are qualities that are productive beyond the virtual. Architecture can bring the virtual to life.

Greg Lynn’s Bloom house is a fantastic example of the way imaging like Scotts could provide collateral for a new way of detailing the architectural frame. The walls bulge and produce fireplaces, or bloat and absorb book cases, architecture becomes exciting and nimble. Architecture becomes highly modeled with inflections, as traces of a nearly absent touch.

Surfaces become more abstract and embedded with responsiveness.

The status of contemporary body is fascinating, it’s less physical but more present, spread thinner and more site-less. I think I’ve shown that the theoretical framework for this transition has long been in the making. But it’s likely to be impossible to verbalize the exact next steps, or order of operations that would result in a de-figured architecture over a disfigured architecture. There are so many people working on this problem that I thought I would close my talk by making some comparisons that I think are useful for locating what I’m after.

De-figured Architecture is not a broken thing.

It’s not composed of shards and splintered spaces.

It’s not an autonomous architecture, nor is it a critical regionalism.

It is not one or many things

It is faceless, But expressive

It’s less about linking

…and more about blending

De-figured architecture communicates beyond its local condition.

And differently from multiple positions. Shifting its posture, and becoming something new. De Figured architecture is less organic, But not mineralogical.

It can be present and absent.

It is more ambiguous…

And highly specific.

I think it’s natural to be unsure where figural architecture will be going, and what role the body will play. This is almost always the case in a paradigm shift. Will our simulated selves inhabit a virtual architecture, or will reality absorb the virtual?

Architecture can relinquish the body, or reclaim its connection to it.

In the end it comes down to this,

Historically man has been the measure of architecture, And architecture has been the measure of culture. This is why there is such a frenzy of activity in the discipline to locate that thing which has been lost. Our foundations have shifted, and as I move towards a post-anatomical figurality, It will be through de-figuring.